Complex Angular Forms Deserve Their Own Classes

Complex Angular Forms Deserve Their Own Classes

Introduction

If you’re anything like I was not that long ago, you’re comfortable with Angular’s reactive forms — you’ve used them to build everything from simple inputs to complex multi-step forms. You know the API, the validators, the workarounds. Most problems feel solvable.

But then you hit a wall: a large form with nested groups, conditional logic, and cross-field behavior. Suddenly, your once-elegant setup becomes verbose, repetitive, and sprawls across hundreds of lines. You try to split things up, but breaking the form into pieces adds unnecessary complexity — especially when it really needs to behave as one cohesive unit.

This is where I started rethinking how I structure my forms. I found an approach that worked well: extending FormGroup to encapsulate logic, keep my components clean, and reuse functionality — without giving up the power of Angular’s reactive system.

⚠️ Disclaimer: Yes, I’m about to extend a public Angular class. And yes, that’s often discouraged in favor of composition. But in this case, I believe it’s the right tradeoff — and I’ll show you why.

If you’re firmly in the “composition over inheritance” camp, hang in there — I’ll also touch on how the same logic could be structured using composition or factory functions, and when that might be a better fit. Either way, I hope this gives you a practical perspective you can apply in your own Angular projects.

The Problem

Reactive Forms in Angular are a great tool — powerful, expressive, and well-supported. But as your forms grow in complexity, you start to feel the friction.

What begins as a clean FormGroup declaration quickly becomes a sprawling forest of controls, nested groups, conditional logic, and interdependent value changes. You wire up subscriptions to patch or reset other fields, manage custom validators, and maybe even keep a few BehaviorSubjects around to control side effects.

Before long, your form file is:

- Several hundred lines long

- Mixing UI wiring with business logic

- Painful to test in isolation

- Repetitive in ways TypeScript can’t help you with

You could try to split the form into smaller FormGroups and recompose them — but in many cases, the form needs to behave as a single unit. Splitting it adds complexity instead of solving it. That’s especially true when validation and value logic depend on sibling controls or deeply nested conditions.

The Inheritance Approach

To reduce repetition and keep my forms readable, I started extending Angular’s FormGroup.

At first, it felt a little wrong — inheritance from framework classes is often discouraged. But in this case, it worked surprisingly well. I was able to:

- Encapsulate subscriptions and conditional logic inside the form class

- Swap nested FormGroups based on selected values

- Add typed convenience methods and getters

- Keep components clean and focused on rendering and interaction

Here’s a simplified example that touches similarities in realistic problems.

Let’s say you’re building a pet preferences form. Based on the selected pet type (dog or cat), you need to dynamically show and manage a different set of controls.

A DogFormGroup for additional information when ‘dog’ is selected:

export class DogFormGroup extends FormGroup<{

barksOften: FormControl<boolean>;

walksPerDay: FormControl<number>;

}> {

constructor() {

super({

barksOften: new FormControl(false, { nonNullable: true }),

walksPerDay: new FormControl(1, { validators: [Validators.min(0)], nonNullable: true }),

});

}

}

And a CatsFormGroup for additional information when ‘cat’ is selected:

export class CatFormGroup extends FormGroup<{

cleansLitterDaily: FormControl<boolean>;

isIndoor: FormControl<boolean>;

}> {

constructor() {

super({

cleansLitterDaily: new FormControl(true, { nonNullable: true }),

isIndoor: new FormControl(true, { nonNullable: true }),

});

}

}

The PetForm uses both:

type PetType = 'dog' | 'cat';

export class PetFormGroup extends FormGroup<{

type: FormControl<PetType>;

info: DogFormGroup | CatFormGroup; // switched dynamically

}> {

private readonly destroy$ = new Subject<void>();

// I like to keep FormGroups readonly

private readonly dogForm: DogFormGroup;

private readonly catForm: CatFormGroup;

// The constructor can take in controls or config — up to you

constructor() {

const dogFormGroup = new DogFormGroup();

super({

type: new FormControl<PetType>('dog', { nonNullable: true }),

info: dogFormGroup,

});

this.dogForm = dogFormGroup;

this.catForm = new CatFormGroup();

this.handleTypeChanges();

}

private handleTypeChanges() {

this.controls.type.valueChanges.pipe(takeUntil(this.destroy$), distinctUntilChanged()).subscribe(pet => {

if (pet === 'dog') {

this.setControl('info', this.dogForm);

}

if (pet === 'cat') {

this.setControl('info', this.catForm);

}

});

}

destroy() {

this.destroy$.next();

this.destroy$.complete();

// when there would be any subscription in the subforms, you can unsubscribe from those too

}

}

As you can see every instance of PetFormGroup will handle its own type changes logic and is encapsulated from other parts of the application. Also note that it’s fully compatible with FormGroup expectations (both in code and templates).

💡 Note: The logic you encapsulate in a FormGroup class isn’t limited to just reacting to valueChanges. You can use it to enable or disable controls, add or remove validators dynamically, reset subsets of the form, or react to status changes — anything related to managing the behavior of the form belongs here. This makes your form class the single source of truth for how the form behaves.

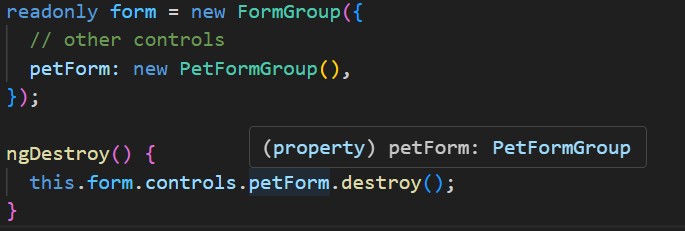

In your Angular components PetFormGroup can be part of a larger form:

@Component(...)

export class SomeClass implements OnDestroy {

readonly form = new FormGroup({

// other controls

petForm: new PetFormGroup(),

});

}

ngDestroy() {

this.form.controls.petForm.destroy();

}

The types of the properties can be inferred through controls.

With this structure:

- Your component doesn’t need to manage subform switching logic.

- Your form class (PetFormGroup) remains the only interface your component cares about.

- Your form class inherits the already familiar interface from Angular’s

FormGroup

This kind of logic would get messy fast if managed directly in the component. Inheritance keeps it modular and expressive.

Adding convenience methods

It is possible to add convenience methods to PetsFormGroup. We already did with destroy. Let’s assume that from an outside source we want to set the age of the pet based on its stage in life:

class PetFormGroup {

// other code

setLifeStage(stage: 'junior' | 'adult' | 'senior' | 'geriatric'): void {

const dogAgeMap = {

junior: 1,

adult: 3,

senior: 7,

geriatric: 12,

};

const catAgeMap = {

junior: 1,

adult: 5,

senior: 10,

geriatric: 14,

};

this.dogForm.controls.age.setValue(dogAgeMap[stage]);

this.catForm.controls.age.setValue(catAgeMap[stage]);

}

}

Now in your component, you can simply do:

@Component(...)

export class SomeClass implements OnDestroy {

readonly form = new FormGroup({

// other controls

petForm: new PetFormGroup(),

});

}

handleSeniorLifeStage() {

this.form.controls.petForm.setLifeStage('senior');

}

ngDestroy() {

this.form.controls.petForm.destroy();

}

And both subforms will be updated appropriately behind the scenes — regardless of which one is currently active.

The Composition Alternative

If you’re not comfortable extending Angular’s FormGroup (since it is cautioned against it), you can achieve a similar structure using composition. Instead of subclassing FormGroup, you wrap it inside your own class and delegate to it.

This avoids tight coupling to Angular’s internal APIs, and it gives you more flexibility if you ever switch to an alternative.

Here’s how the same pet form could be written using composition:

export class PetFormGroupWrapper {

private readonly destroy$ = new Subject<void>();

readonly formGroup: FormGroup<{

type: FormControl<PetType>;

info: DogFormGroup | CatFormGroup;

}>;

private readonly dogForm = new DogFormGroup();

private readonly catForm = new CatFormGroup();

constructor() {

this.formGroup = new FormGroup<{

type: FormControl<PetType>;

info: DogFormGroup | CatFormGroup;

}>({

type: new FormControl<PetType>('dog', { nonNullable: true }),

info: this.dogForm,

});

this.handleTypeChanges();

}

private handleTypeChanges() {

this.formGroup.controls.type.valueChanges.pipe(takeUntil(this.destroy$), distinctUntilChanged()).subscribe(pet => {

if (pet === 'dog') {

this.formGroup.setControl('info', this.dogForm);

}

if (pet === 'cat') {

this.formGroup.setControl('info', this.catForm);

}

});

}

setLifeStage(stage: 'junior' | 'adult' | 'senior' | 'geriatric'): void {

// same logic as before, updating both subforms

}

destroy() {

this.destroy$.next();

this.destroy$.complete();

}

}

In the component, you’d use formGroupWrapper.formGroup instead of just form:

@Component(...)

export class SomeClass implements OnDestroy {

readonly formWrapper = new PetFormGroupWrapper();

readonly form = new FormGroup({

// other controls

petForm: formWrapper.formGroup,

});

}

handleSeniorLifeStage() {

this.formWrapper.setLifeStage('senior');

}

ngDestroy() {

this.formWrapper.destroy();

}

The structure is similar.

So Why Inheritance over Composition?

Look at your recent Angular projects and let’s be honest: did you really take the time to build a complete abstraction over Angular’s Reactive Forms, or are your forms already tightly coupled to them — with FormGroup, FormControl, and [formGroup] bindings scattered throughout your codebase?

In my experience, it’s always the latter.

So how hurtful is inheritance really?

Yes, extending a framework class breaks some clean architecture rules. But in this case, the indirection felt like a bigger trade-off. Especially when your real goal is just to keep logic grouped and forms readable.

A Note on Lifecycle Management

In the examples above, we included a destroy() method to manually clean up subscriptions via a destroy$ subject. This works fine, but it does rely on you remembering to call destroy() at the right time — which can be easy to forget.

If you’re already using takeUntil(this.destroy$) in your components or services, you can simplify this by injecting the lifecycle observable directly into your form class:

💡 This also works seamlessly with the composition approach — you can pass the same

destroy$observable down to any subform or wrapper you create, making cleanup consistent and centralized.

export class PetFormGroup extends FormGroup<...> { // it would also work with the composition approach

constructor(private destroy$: Observable<void>) {

super({

type: new FormControl('dog'),

info: new DogFormGroup(destroy$)

});

this.dogForm = this.controls.info;

this.catForm = new CatFormGroup(destroy$);

this.handleTypeChanges();

}

private handleTypeChanges() {

this.controls.type.valueChanges

.pipe(takeUntil(this.destroy$), distinctUntilChanged())

.subscribe(pet => {

if (pet === 'dog') {

this.setControl('info', this.dogForm);

} else if (pet === 'cat') {

this.setControl('info', this.catForm);

}

});

}

}

Now, when the component completes its destroy$, the form unsubscribes automatically — no destroy() call needed. This is a nice refinement when your form’s lifecycle is tied closely to a component or service, and you’re already managing teardown there.

This pattern ensures that all parts of your form tree respond to the same lifecycle signal, making it easier to manage memory and avoid leaks in complex forms.

Summary & Conclusion

In large, complex Angular forms, verbosity and duplication quickly become the enemy. Reactive Forms are powerful, but when logic becomes tightly coupled with deeply nested structures, readability and maintainability start to suffer.

This article showed an approach to simplify that complexity: extending FormGroup directly and bundling logic into purpose-driven classes. Yes, inheritance is usually discouraged with Angular constructs, and yes, composition is the more framework-agnostic path. But if you’re already married to Reactive Forms — and let’s be real, most of us are — a little coupling can go a long way in improving clarity and reusability.

You saw how using a custom FormGroup subclass helps you:

- Keep related logic together (subscriptions, derived controls)

- Avoid repetition

- Make large forms easier to split and reason about

Composition remains a solid option — safer in the long term, and more flexible if you ever need to swap out Angular forms entirely. But if inheritance gives you simpler, more maintainable code right now, that’s not something to dismiss lightly.

At the end of the day, the best choice is the one that works well for your team, your codebase, and your actual constraints — not just the textbook best practice.

A final suggestion

If your reactive forms are getting complex with nested or extended FormGroup’s, you might consider custom form controls using ControlValueAccessor. This approach often leads to clean, reusable, and easy-to-maintain form components.